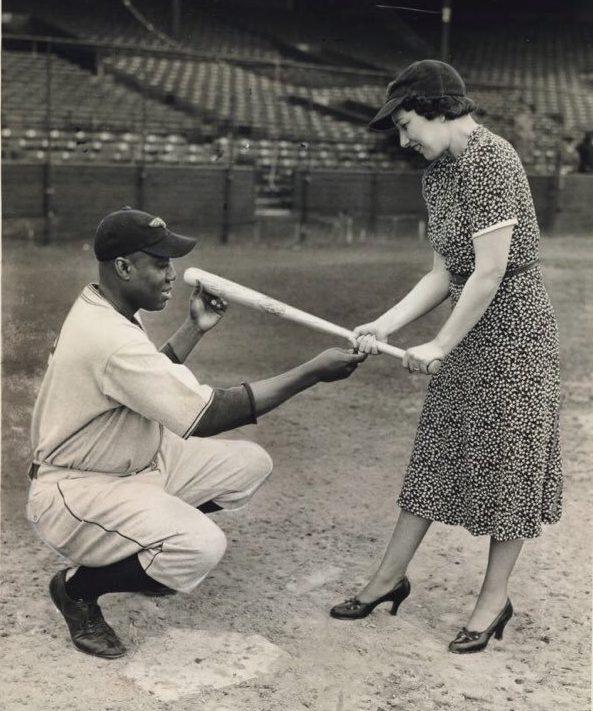

Effa Brooks grew up watching baseball at Yankee Stadium. It was there at the 1932 World Series that she met black baseball man Abe Manley. The two were married in June, 1933 and began a partnership that lasted until Abe’s death in 1952.

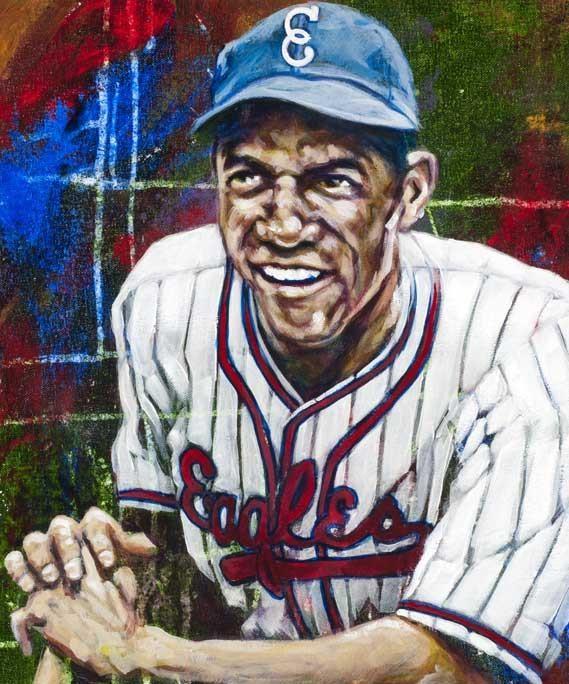

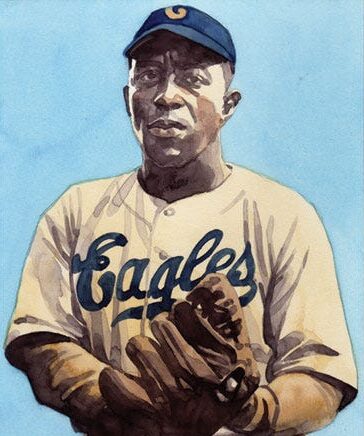

According to SABR, the National Negro League owners approved Abe as owner of the Brooklyn Eagles in November, 1934. Effa ran the day-to-day operations and jumped right in.

She convinced New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to throw out the first pitch on Opening Day. The Eagles finished the season in sixth place in the eight-team league.

After the 1935 season, the Manleys gained control of the Newark Dodgers. They combined the assets with the Brooklyn Eagles and formed the Newark Eagles.

During her reign as co-owner, Effa fought to legitimize the Negro Leagues. She handled contract negotiations and served as the team’s traveling secretary.

To elevate her team and the league, Manley purchased a team bus for comfortable and reliable travel. She worked to secure the best possible hotels on the road. Everything about her operations was professional.

In the offseason, she maintained contact with the players and helped them with outside employment.

Outside of baseball, Effa was a strong advocate for Civil Rights. She organized boycotts of white businesses in Harlem that didn’t employ people of color. Her work paid off as stores changed their hiring practices. At the Eagles home park Ruppert Stadium, the ushers wore sashes that said, “Stop Lynching”. She fought for rights her entire life.

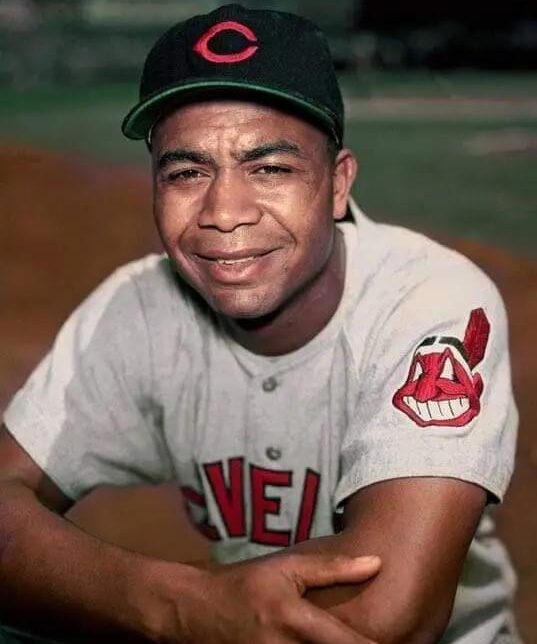

Manley’s Newark Eagles roster boasted some of the best talent in the Negro Leagues. Hall of Famers Ray Dandridge, Willie Wells, Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Biz Mackey, and Mule Suttles all wore the Eagles uniform.

The crowning moment of the franchise came in 1946. The Eagles won the National Negro League championship and met the ANL champion Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League World Series.

A formidable squad, the Monarchs were led by future Hall of Famers Satchel Paige, Hilton Smith, and Willard Brown. At first base was 34-year old Buck O’Neill.

Manley’s Eagles outlasted Kansas City in an epic seven-game tilt and were crowned champions of the Negro Leagues.

Drastic changes were in store for Manley and the Negro Leagues. Jackie Robinson reached a minor league deal with the Dodgers and left the Monarchs to play for Triple-A Montreal in ’46. When Robinson debuted with the Dodgers in ’47, the demise of the Negro Leagues was imminent.

Soon Bill Veeck‘s Indians expressed interest in the Eagles’ Larry Doby. Manley brokered the sale for $10,000 and another $5,000 if he remained on the Tribe’s roster for 30 days. Effa also negotiated Doby’s salary in Cleveland as part of the deal. She secured the young player a 25% increase over his deal with Manley’s Eagles.

The move set a precedent that made white baseball owners compensate their Negro League counterparts for players.

Though the Manley’s sold the Eagles in 1948, Effa remained close to the game. She supported the inclusion of Negro League players in Cooperstown, writing to MLB owners for their support.

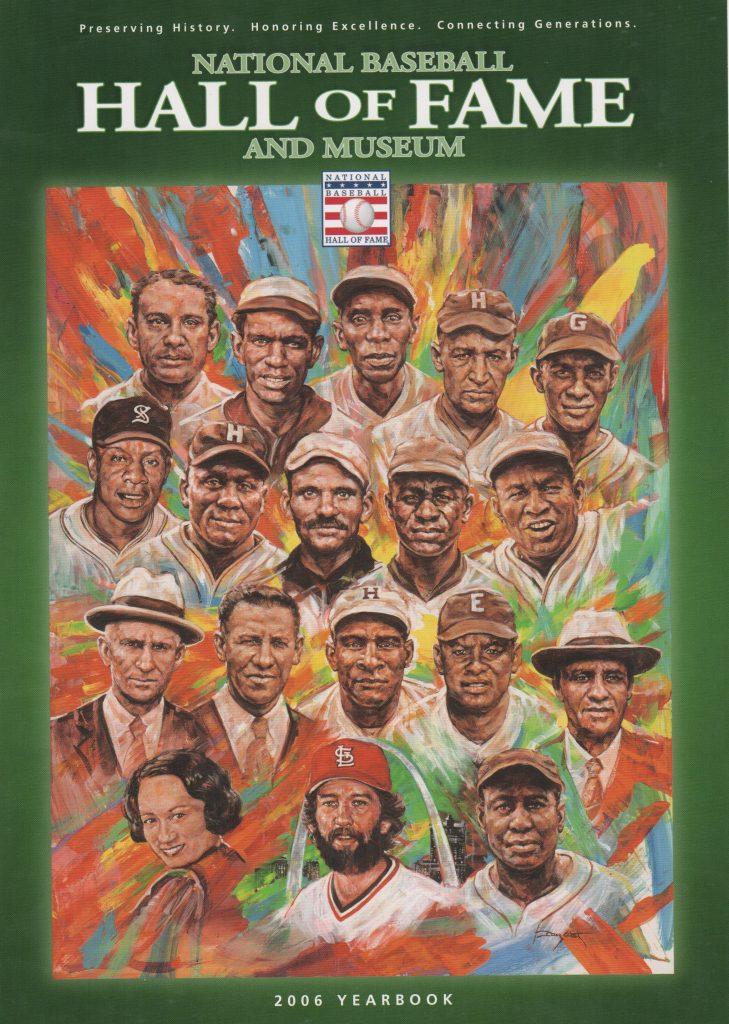

The Hall responded by creating the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues to elect Negro League players. From 1971-1977 nine players were given plaques.

By 1981 Manley was in her 80s and in poor health. She passed away on April 15, 1981. Her tombstone reads simply, “She Loved Baseball.”

Manley was given baseball’s highest honor when she was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2006. She is the only woman with a plaque in Cooperstown.

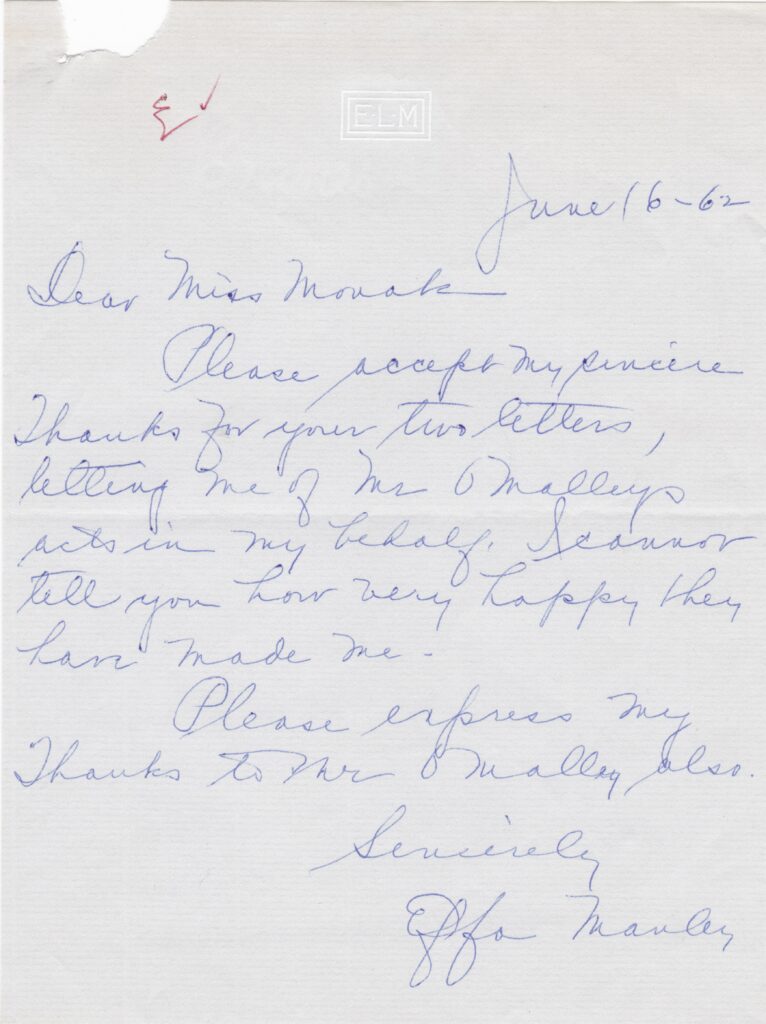

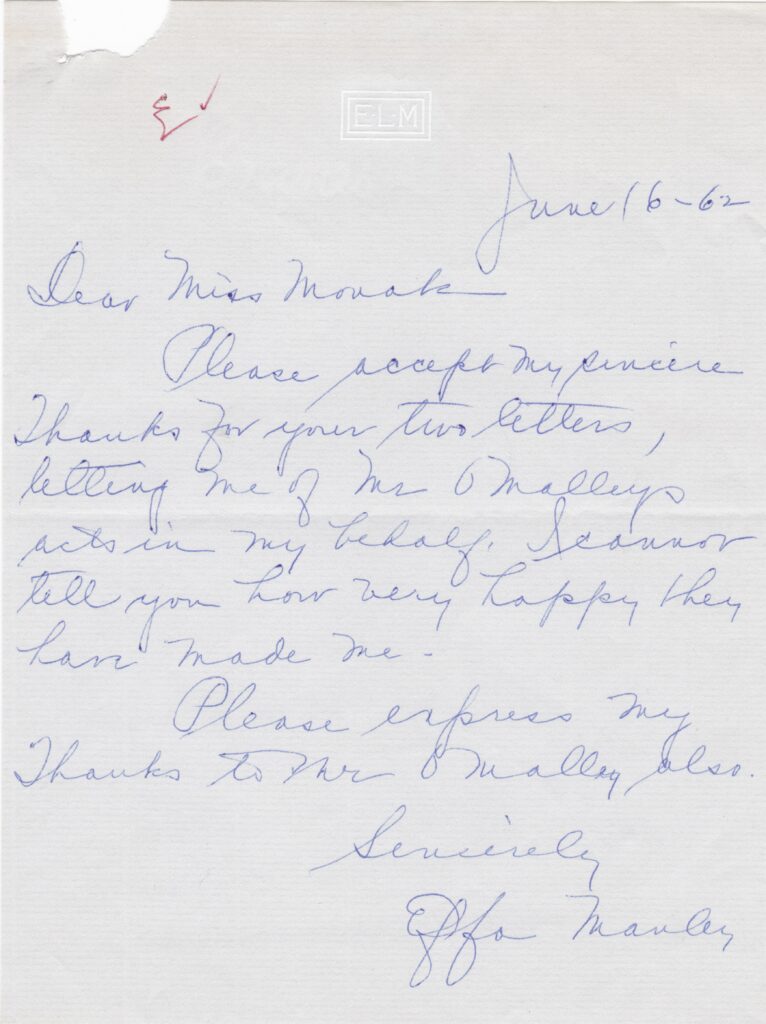

In the collection is this handwritten letter signed by Hall of Fame executive Effa Manley. Penned to Dodger owner Walter O’Malley, the correspondence is dated June 16, 1962, two months after the opening of Dodger Stadium

Manley writes to O’Malley’s longtime secretary Edith Monak, “Please accept my sincere thanks for your two letters letting me know of Mr. O’Malley’s acts on my behalf. I cannot tell you how very happy they have made me.

“Please express my thanks to Mr. O’Malley also.”

Though the specific issue to which Manley refers is lost to history, the letter shows her continued link to baseball nearly fifteen years after selling her Negro League club.