America’s Greatest Generation: The story of a few good men

Famed historian on American Culture Jacques Barzun said in 1954, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball”. For many who love the game, this remains true today. Baseball reflects American culture, our hopes and dreams.

Among the eras when baseball and our country’s culture was most intertwined was during the Second World War. Of the more than 16 million Americans who served in World War II, nearly 40% were volunteers. Men chose to serve out of a sense of honor, allegiance and loyalty to the flag and the ideals it represents. They formed “America’s Greatest Generation” – a cohort defined by a shared unselfish sense of the greater good, of duty and honor.

Four ballplayers do their part

The heroism of Ted Williams and Bob Feller during the War is well-documented. Those two men weren’t alone in their service. This is the story of wartime contributions of a few lesser-known ball players: Lou Brissie, Buddy Lewis, George Earnshaw, and Al Niemiec. These men, like many Americans of the era, felt an undeniable drive to do the right thing. They exemplified the American culture and spirit of their time. Though their stories seem heroic today, in their era it was much closer to standard practice.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the GI Bill had a provision that guaranteed men employment and pay in their former jobs upon their return to civilian life after the war. For ballplayers there was no guarantee their ability to play at the professional level would remain intact after their time in the military. They served anyway.

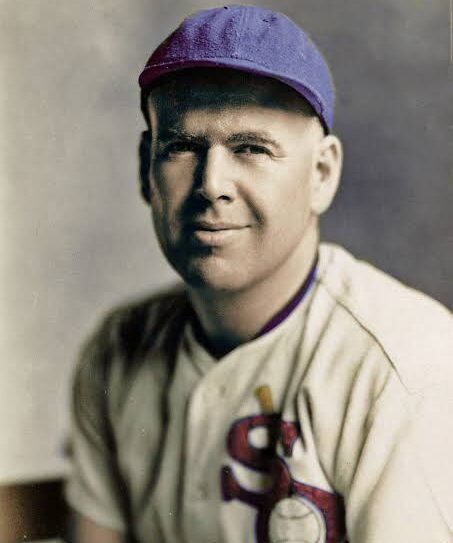

Lou Brissie is the youngster of the quartet. He graduated from Ware Shoals High School in 1941, and signed with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics at age 17. The highly-regarded 6’4” 210-pound southpaw was on the fast track to the bigs but Lou had more important things on his mind. He wanted to fight for his country.

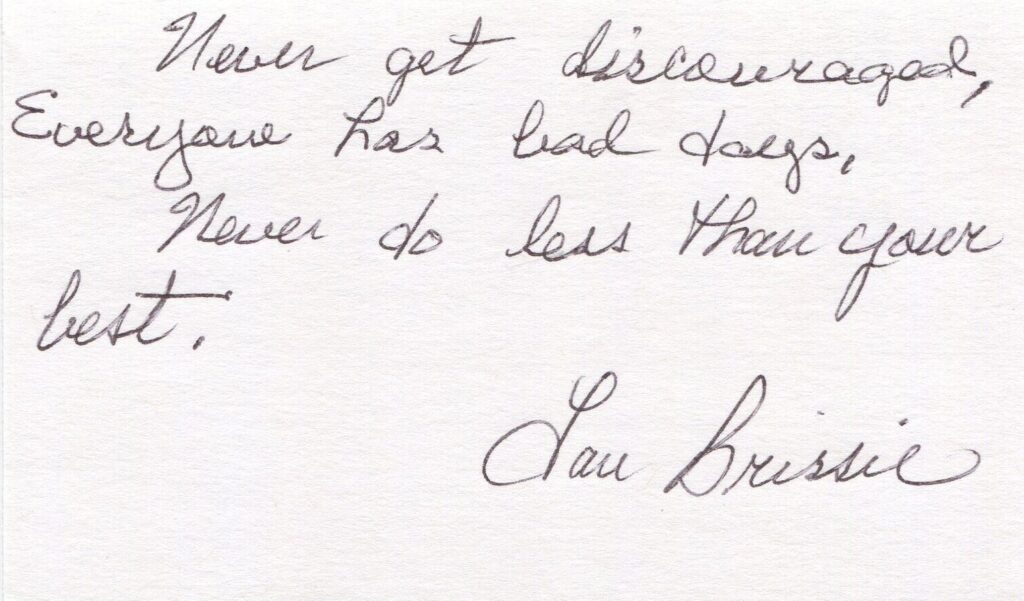

Twice Brissie tried to sign up before his 18th birthday, but his parents wouldn’t sign the paperwork for him to enlist. Brissie explained later, “My dad knew I never did less than my best. His view about my enlisting was, ‘You’ll be in there soon enough.’” The father knew his son. Days after his 18th birthday in 1942, Lou enlisted in the Army.

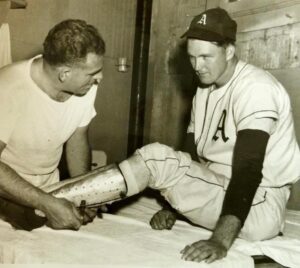

Brissie’s leg is broken in 30 places

Lou saw combat early and often. Two years into his service he experienced a life-changing event. On the third anniversary of Pearl Harbor, corporal Brissie and the 351st infantry regiment fought the Nazis in northern Italy’s Apennine Mountains.

Heavy artillery fire killed or wounded 8 enlisted men and three officers, Brissie among them. A German shell exploded near Brissie, spraying shrapnel throughout his body. Metal from the shell pierced his right shoulder, both hands, and both thighs. Most serious among his injuries was Lou’s left tibia and shinbone which were broken in 30 places. Brissie lost consciousness in a muddy creek bed. Left for dead, Brissie was found passed out several hours later. Field surgeons suggested amputating his leg. Brissie wouldn’t bear the thought.

“I’m a ballplayer! You’ve got to find another way,” he exclaimed.

Over the next three days Brissie was sent to various hospitals, refusing the prescribed amputation. Finally Dr. Wilbur Brubaker in the Naples Army hospital gave Brissie hope and agreed to work on the shattered limb.

It was all the now-20-year old Brissie needed. “Once he operated on me,” Lou told Baseball Digest, , “I didn’t wonder if I could make it back to pitch, but how I could do it.”

His leg was tattered and in disarray but his spirit was unbowed.

Twenty-one days after the shell did its damage Brissie received a letter from Mack. Brissie’s determination comes through in his description of the correspondence: “Mr. Mack told me that my duty now was to try to get well, and whenever I felt I was ready to play, he would see I got the opportunity. That meant an awful lot to me. It was a tremendous motivator.”

The corporal is a big leaguer at last

Two years, 23 leg operations and 40 blood transfusions later, Brissie continued his dream. “They had to reconstruct my leg with wire and a metal plate,” he said. Still he returned to the mound. Pitching with a leg brace and constant pain, Brissie went 23-5 with a 1.91 ERA in his only minor league season in 1947.

In September the Athletics called him up. Lou Brissie made his big league debut on September 28 with a 7-inning start at Yankee Stadium. The corporal with the shattered leg was a Major Leaguer at last. Two years later he pitched three innings in the American League’s 1949 All Star Game victory.

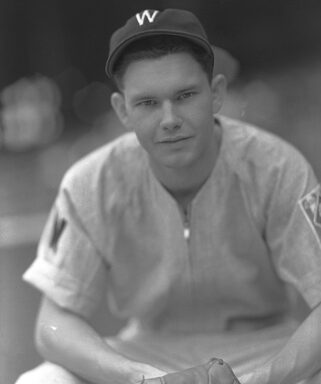

Ty Cobb, Mel Ott, Al Kaline, Freddie Lindstrom, and Buddy Lewis

While Brissie was just starting his career when the War intervened, Washington Senators third baseman Buddy Lewis was an established star. Before the war, Lewis just may have been on a Hall of Fame trajectory. A teenage sensation, he was the 5th-youngest player to amass 1,000 hits. Indeed, all four ahead of him are in Cooperstown – Ty Cobb, Mel Ott, Al Kaline, and Freddie Lindstrom.

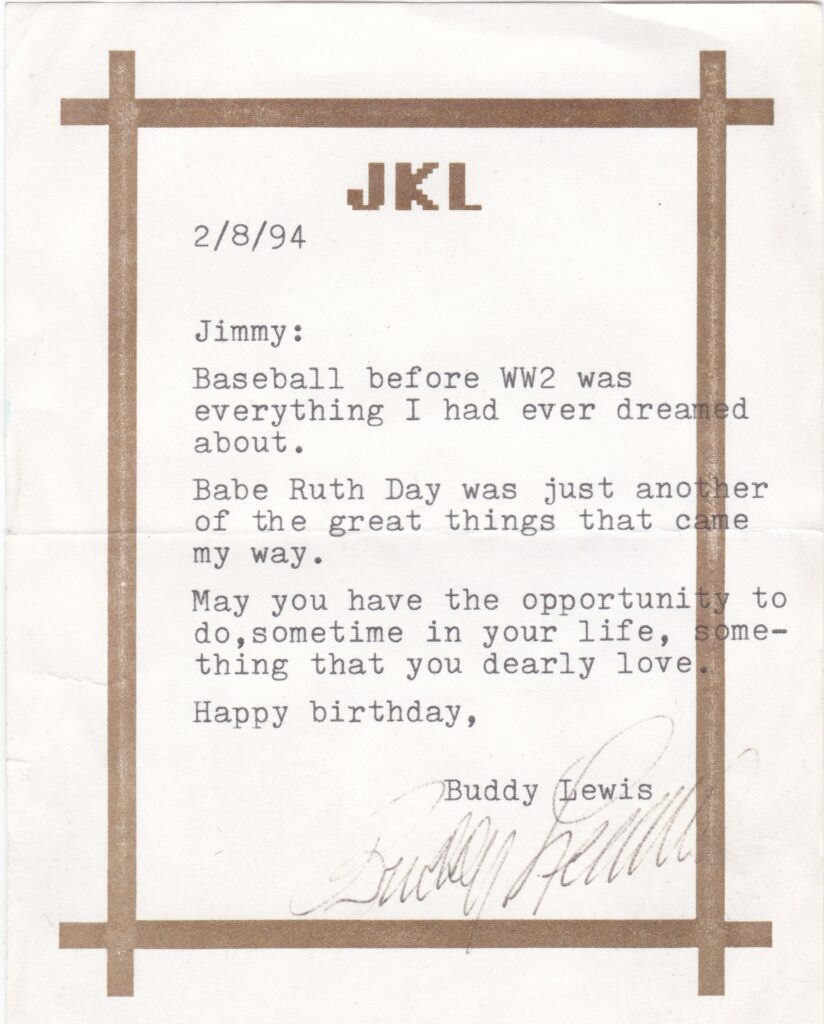

Lewis received MVP votes in two of his first three big league seasons. It didn’t start that way. As a 19-year old Lewis broke in with the Clark Griffith’s Senators. Sensing the young player was homesick, Griffith took Lewis under his wing and often invited him to family dinners to ease his loneliness. Lewis got comfortable and performed at a high level. By the end of his age-24 campaign in 1941, Lewis owned a .305 average. Baseball before World War II was everything he ever dreamed about. Cooperstown seemed possible. Caring more about duty than about fortune and fame, Lewis enlisted into the US Army to help the war effort

Lewis names his plane after the Senators owner

With great eye-hand coordination, Lewis was ticketed to fly a clunky C-47 transport plane he named “The Old Fox” after Griffith who he admired so much. As a tip of the cap to Hall of Famer Griffith, Lewis painted the moniker on the nose of his aircraft.

In the China-Burma-India Theater, Lewis piloted a The Old Fox “over the hump” – a dangerous route over the Himalayas and through enemy fire. Lewis’ commanding officer advised him to carry a baseball with him on missions. The Japanese love of the American game just might make captivity less harsh for a big leaguer player. He was also told to carry cocaine in case the Burmese natives got to him first. The gift would increase the chances of cooperation.

Fortunately Lewis never needed that baseball or the cocaine despite flying 392 missions. His service and valor earned many commendations, among them the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with oak leaf clusters.

Baseball is never the same for Lewis after the war

When Lewis returned to civilian life, father-figure Clark Griffith welcomed him back to the team. Lewis wanted to make Griffith proud but after the horrors he’d seen in the War, Lewis’s perspective changed.

“When I came back from the war, my philosophy of life was completely different. I had changed so much that baseball didn’t mean as much to me as it did before the war.” He left the game 51 days after his 33rd birthday. Lewis had 1,112 hits and a .305 average at age 24. After that he totaled 481 hits. He never regretted his decision to serve his country.

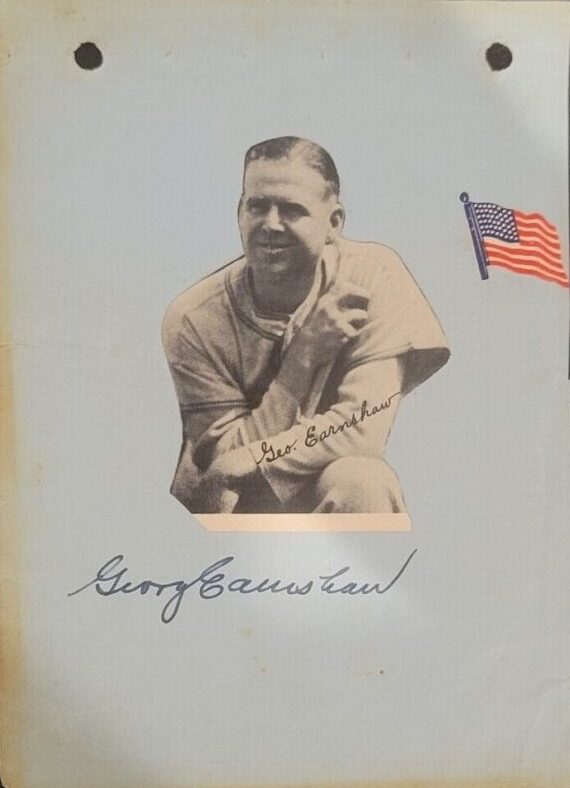

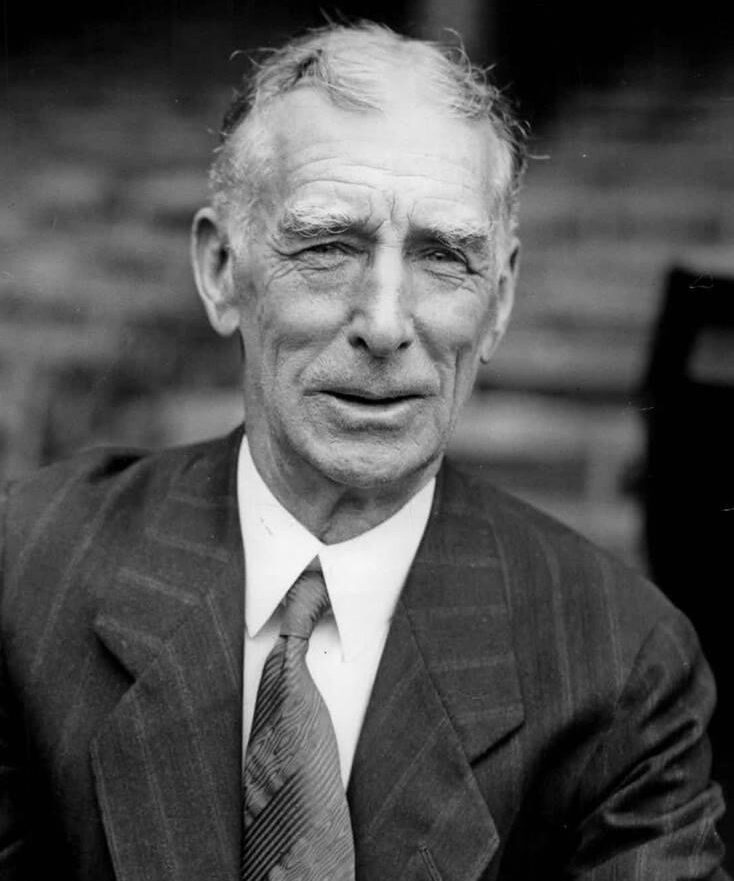

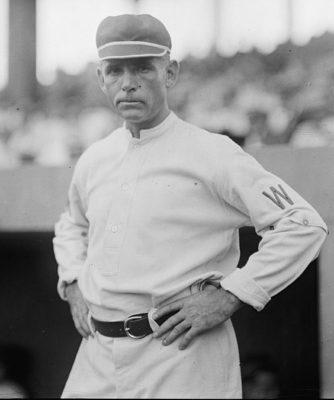

George Earnshaw chooses service to his country

Pitcher George Earnshaw was 16 years older than Lewis. The three-time 20-game winner and two-time World Series champion retired in 1936. Four years after Earnshaw hung up his spikes, the United States enacted the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. In preparation for World War II, the act required all men between the ages of 21 and 36 to register for the draft. As a 41-year old, Earnshaw was exempt from registering. Many would’ve rejoiced.

Not Earnshaw. Five months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the father of three volunteered for service in the Navy.

Assigned to the Jacksonville Naval Air Station, Earnshaw was selected to manage the baseball team. He pitched and piloted them to a 35-12 record in 1942. Later that year he was chosen as a coach of the Navy All Star team that was slated to play a game in Cleveland against active stars from the American League.

The former pitcher chooses battle over baseball

In the months before the game, the Navy commissioned the aircraft carrier Yorktown. Volunteers were taken to serve aboard the new ship. With a cushy stateside military baseball assignment already in his pocket, Earnshaw opted instead for action in the Pacific Theater.

Just days after his 44th birthday Lieutenant Commander Earnshaw and the Yorktown took part in Operation Hailstone, a carrier raid on Truk Island in the Pacific. In a fierce fight Earnshaw was at his best. His valor was aptly described in the commendation Earnshaw received from Admiral Chester Nimitz. “With exceptional ability and judgment and considerable calmness, he directed effective anti-aircraft fire against three fast, low-flying torpedo planes and contributed directly in saving his ship from serious damage.” Earnshaw was later awarded the Bronze Star for heroism.

He left the military in 1947 with the rank of Commander with little fanfare. The 1929 AL wins leader with two World Series rings, George Earnshaw’s athletic greatness was surpassed only by his patriotism and sense of duty to his country as a World War II hero. Like Lou Brissie and Buddy Lewis, Earnshaw was a product of his generation.

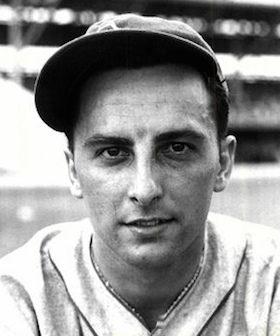

Al Niemiec holds baseball accountable

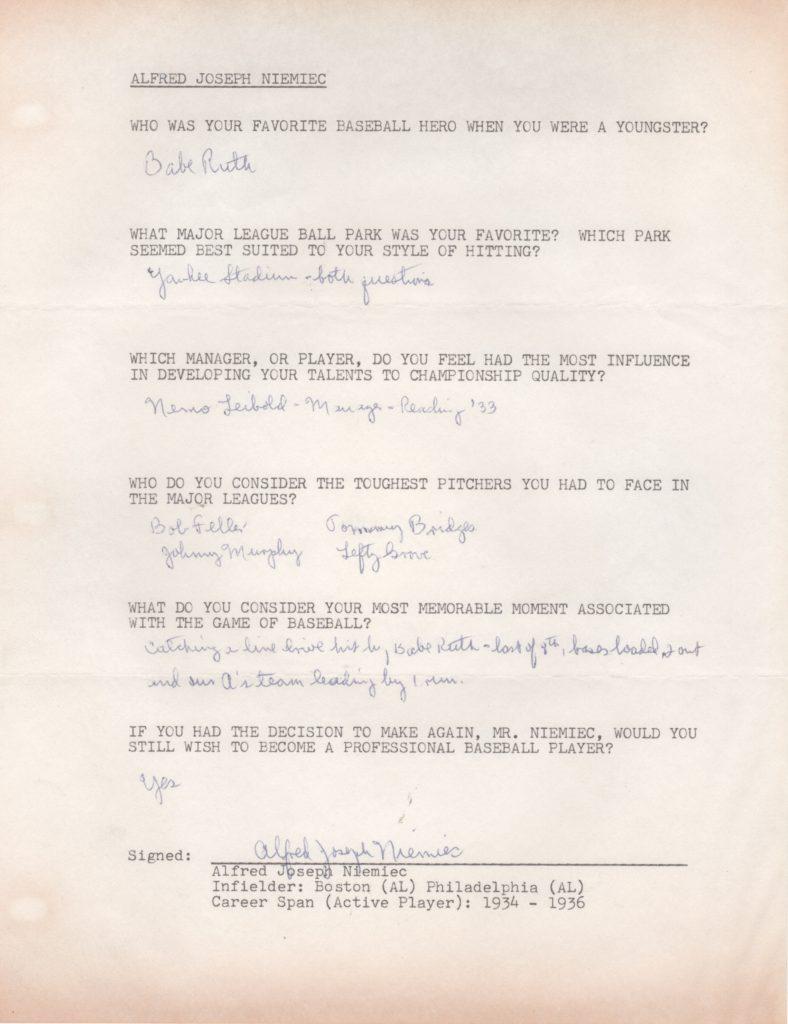

The final man of this foursome is of Al Niemiec whose sense of duty was equally strong. A veteran of more than 1,000 professional games – only 78 at the big league level – Niemiec likewise served in the war. By the time the conflict was resolved, Niemiec was an officer. Al stayed in the Navy until his honorable discharge in 1946, then reported back to the Seattle Rainiers hoping to resume his baseball career.

Two years removed from his last game and now 35 years old, Niemiec was beaten out by a younger man and released. Knowing that the GI Bill guaranteed previous employment and pay for one year, Niemiec sued Baseball for violating the Act.

The courts side with Niemiec

Judge Lloyd Black of the US District Court in the Western District of Washington handed down his ruling: “…baseball is the American game [and] certainly, then baseball ought to bear its share of any burden in being fair to service man. There are few institutions in American life which ought to feel a greater obligation. If Mr. Niemiec and all the others had failed at their job, there would be no American manager of any baseball…If the Nazis permitted baseball, it would not be an exhibition any of us liked.” Black ruled for Niemiec and all returning baseball players.

Niemiec’s legal victory gained monetary compensation for many men who fulfilled their duty when their country needed them most. The courts held America accountable in taking care of her own.

Baseball always reflects the culture we live in

Our national pastime has always reflected America’s culture, good and bad. During World War II Lou Brissie, Buddy Lewis, George Earnshaw and Al Niemiec were shining examples of America’s Greatest Generation. They saw their lives through a lens of responsibilities and obligations as a way to earn and protect their rights and privileges. These men exemplified America’s culture of the era in their roles in World War II and the aftermath. They just happened to be big league baseball players.

This story was originally presented at the Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2024 Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture.

Reach Jim Smiley, the author of this story at CooperstownExpert@gmail.com

Be sure to check out CooperstownExpert.com, the internet’s leading website for the display of museum-quality baseball autographs.